In early May 1944, the 442nd was sent to Europe, and the following month met up with the 100th Infantry Battalion, which was formally attached to the 442nd two months later. Within a month, Chaplain Yamada was accompanying the men into battle. His driver, Edward Yamasaki, recalled that “Chappie” — as he referred to Yamada — “was an experienced minister who knew just how to talk to the boys,” many of whom, like Yamada, had come from rural plantations and spoke Pidgin English. It was something Yamada would be called upon to do with increasing frequency as the number of killed and wounded continued to climb.

On September 1, 1944, Yamada was seriously injured while crossing the Arno River in a jeep to pick up the bodies of dead soldiers. The jeep hit a mine and exploded, catapulting it 30 feet into the air. Yamada was thrown from his seat and suffered severe shrapnel wounds. He was the only man to survive the incident. By the end of September, he was back with his men.

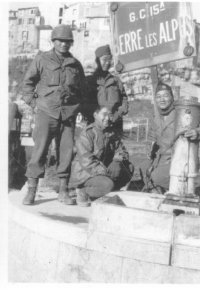

In mid-October, the 442nd was sent to northeastern France to liberate several small towns in the Vosges mountains near the French-German border. Just days after the battle-fatigued unit had liberated the French towns of Bruyeres, Biffontaine and Belmont, Yamada accompanied the men back into the bitter cold Vosges forests to help rescue 211 soldiers of the 141st Infantry — originally the Texas National Guard — who were surrounded by German troops. Critically low on food and ammunition, the 100th/442nd was called in to rescue the “Lost Battalion.” It would take five, long days for the AJA soldiers to free the 141st. The human toll for the 100th/442nd was huge. Yamada, who personally visited “five or six hundred” wounded men, wrote of the difficulty of ministering “to the breaking soul.”

Chaplain Yamada remained with the 442nd until October 1945. After returning to Hawaii, Yamada requested a six-month leave from the ministry so he could help the returning soldiers adjust to civilian life in Hawaii. His thoughts were always with the men with whom he had served and he used the time off to help his men purchase land to build homes and to establish businesses of their own. He also advocated for veterans cemeteries on each island.

When he returned to the pulpit, he was named pastor of the Church of the Holy Cross in Hilo on Hawaii island.

In the larger community, he advocated for the establishment of a University of Hawaii campus in Hilo and worked to bring opera singers and noted musicians to Hilo.

Masao and Ai Yamada were also orchid hobbyists who spent much of their free time creating orchids hybrids — a pastime he described as “orchid therapy.” They had been hybridizing orchids from their years in Hanapepe before the war. Yamada found that teaching people with depression or other emotional conditions how to select and breed orchids took their mind off their own problems and seemed to give them a reason to live. During their five years in Hilo, Chaplain Yamada gained recognition in the orchid world as both a grower and for his advanced breeding techniques.

In 1955, a dispute with members of his congregation over the church’s direction led Reverend Yamada to resign from the Church of the Holy Cross. He and his wife relocated to Oahu, where he worked as the chaplain of the Hawaii State Hospital, an institution for the mentally ill, until he retired.

Chaplain Masao Yamada died on May 7, 1984. He is interred at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific at Punchbowl among the hundreds of Japanese American Nisei with whom he served.

— by Michael Markrich

Michael Markrich is a Honolulu-based researcher, writer and editor. He and Monica Yost co-edited the memoirs of Chaplain Israel Yost, who served the first group of Japanese American soldiers in World War II. The book, “Combat Chaplain: The Personal Story of the World War II Chaplain of the Japanese American 100th Battalion,” was published by the University of Hawaii Press in 2006.

.